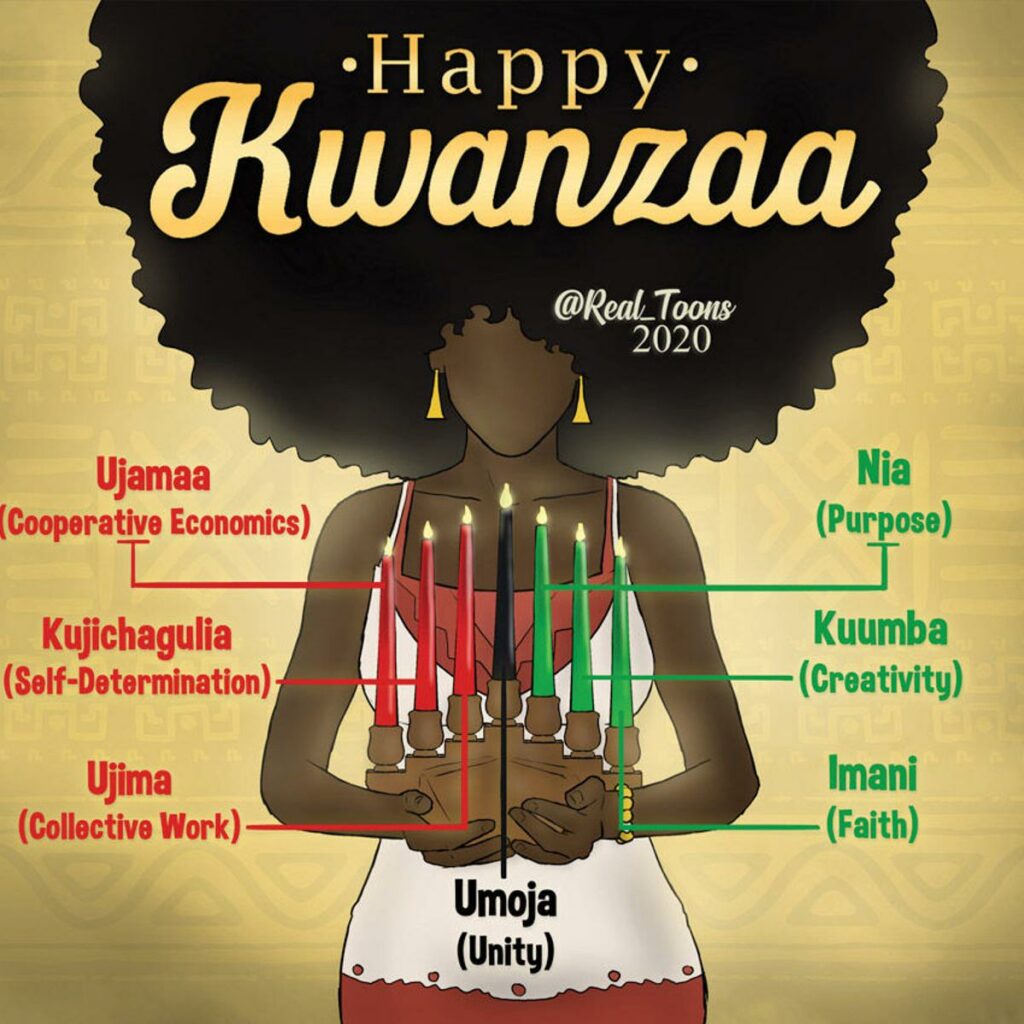

What do you know about Kwanzaa? Minimally, I hope you know that the week-long celebration honoring African-American history and culture begins the day after Christmas and ends on New Year’s Day. For details on its origin, I recommend this post on the blog Miss Higgi Says. What I want to highlight here are the seven principles of Kwanzaa, known as the Nguzo Saba:

1. Umoja (Unity): To strive for and to maintain unity in the family, community, nation, and race.

2. Kujichagulia (Self-determination): To define and name ourselves, as well as to create and speak for ourselves.

3. Ujima (Collective work and responsibility): To build and maintain our community together and make our brothers’ and sisters’ problems our problems and to solve them together.

4. Ujamaa (Cooperative economics): To build and maintain our own stores, shops, and other businesses and to profit from them together.

5. Nia (Purpose): To make our collective vocation the building and developing of our community in order to restore our people to their traditional greatness.

6. Kuumba (Creativity): To do always as much as we can, in the way we can, in order to leave our community more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it.

7. Imani (Faith): To believe with all our hearts in our people, our parents, our teachers, our leaders, and the righteousness and victory of our struggle.

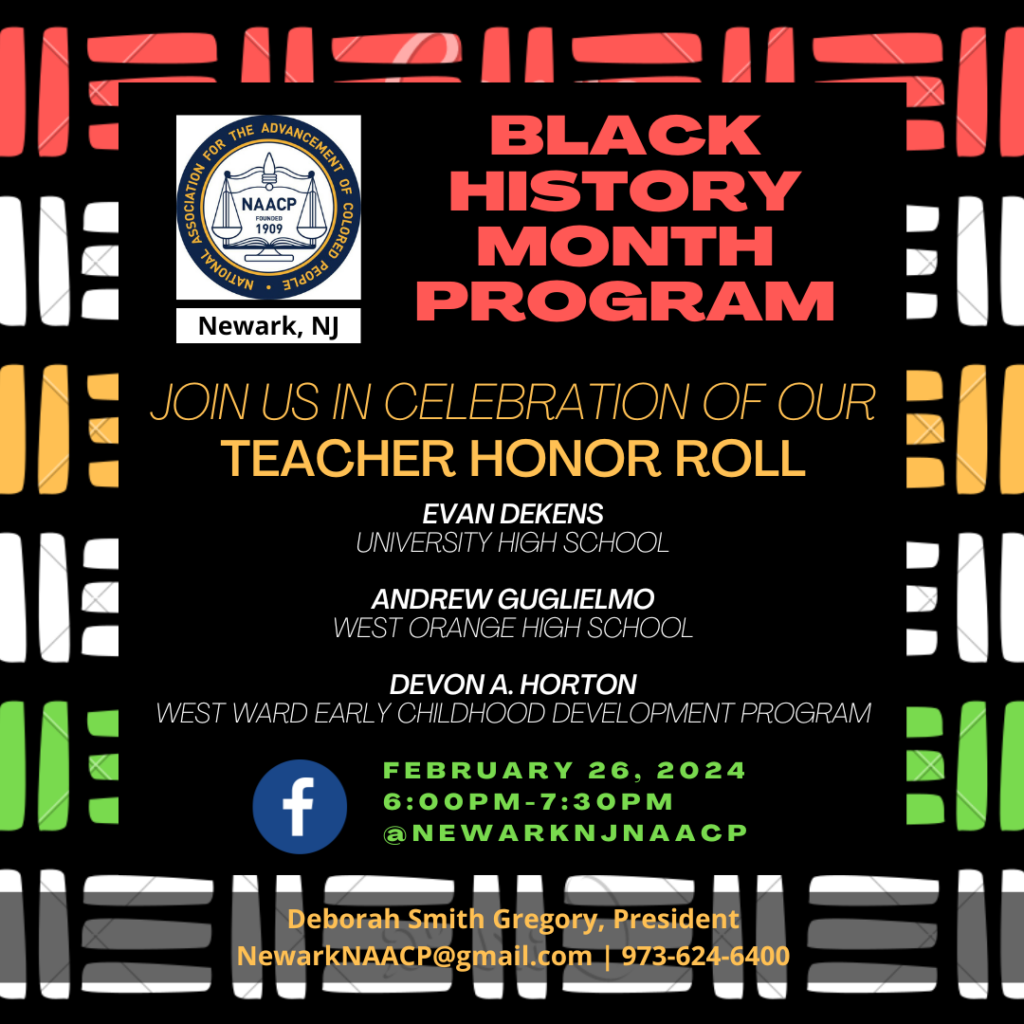

In 2022, NAACP Newark instituted the Teacher Honor Roll, where we recognize educators for their commitment to centering Black History in the education of our children. This year we included a question on the submission form that asked the educators to explain how at least one principle of Kwanzaa is demonstrated in the teaching artifacts they submitted.

Imagine if these principles were instilled in our public education system, if it were the norm for teachers to consider them every time they planned a lesson. Being derived from various African harvest traditions, the implementation of the Nguzo Saba in schools would be an example of an Afrocentric curriculum and what Dr. Molefi Kete Asante names as a revolutionary pedagogy:

“[T]he purpose of education for the revolutionary pedagogist is to prepare students to live in an interconnected global world with personal dignity and respect for all other people as human beings with the same privileges that one seeks for oneself while preserving the earth for those who will come afterwards” (p. 9).

The Nguzo Saba represents African Diasporan cultural continuity–the acknowledgement that African ideas, concepts, and knowledge exist wherever African people are located, not solely on the African continent.

In his scholarship, Dr. Asante highlights the necessity of Afrocentricity for the education of Black children, which means centering Africans in our historical narratives as agents. Other education scholars as well emphasize teaching from students’ cultural frame of reference. Dr. Joyce E. King and Dr. Ellen E. Swartz define Heritage knowledge as a group’s cultural memory, an important concept that aligns with the Adinkra symbol Sankofa (to go back and fetch). To use Heritage knowledge as a foundation of one’s teaching practice is to foster a sense of belonging for students. Neoindigeneity, a term elucidated by Dr. Chris Emdin in his popular book For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and the Rest of Y’all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education, refers to the cultural and spiritual connection of people of the Diaspora and plays a key role in reality pedagogy, “an approach to teaching and learning that has a primary goal of meeting each student on his or her own cultural and emotional turf” (p. 27).

While having the ability to recite the Nguzo Saba has its merits, living these principles is another matter. For Afrocentricity to have a resounding impact on our public education system, we will have to reorient the dominant way of thinking. Eurocentricity has us believing saying “I’m Black and I’m proud” is synonymous with saying anti-White. We see a parallel in the “All Lives Matter” retort to “Black Lives Matter.” This is because Eurocentric logic is inherently anti-Black and built on hatred and a myth of White racial superiority. It believes that in order to love oneself, you must denigrate others. Afrocentricity is not the flip side of the coin. Afrocentricity disrupts that way of thinking because it knows liberation is rooted in love, because to be self-determined does not take away from anyone else. Since education is a social institution as much as an academic one, we have a responsibility to socialize our children not in tolerance of one another but in love of one another. There is no such thing as neutrality when it comes to value systems. Eurocentricity is embedded in the very foundation of the U.S. public education system; it’s time is up. Afrocentricity has the promise of deep intellectual development for all children, not only Black children.

This is not a new conversation, but it is important to highlight at this time because of a recently “decided” court case about school segregation in New Jersey. School desegregation efforts across the nation have shown that the law doesn’t change segregation; people have to want integration. Dr. W.E.B. DuBois’s metaphors of the veil and double consciousness remain deeply rooted in U.S. society and anti-Blackness denies Black folx our humanity. Without other interventions to the socioeconomic sphere, such as affordable housing and housing integration as well as wealth gap redress/reparations, mass voluntary integration is dead on arrival. For those who are willing, the narrative of school integration cannot be one characterized by numerical representation and busing. We need remedies that address curriculum and pedagogy (teaching and learning). What could this look like? Dr. Gholdy Muhammad’s Historically Responsive Literacy (HRL) framework is an example. Dr. Muhammad bases HRL on the history of Black literary societies of the 19th century and puts forward four goals for instructional design: identity development, skills development, intellectual development, and criticality–all in the context of joy. Imagine that! Centering joy in our children’s education, not for play play, but fa real real.

To be clear, the U.S. public education system is working exactly the way it has been designed to work. And it is not the responsibility of the schools to teach Black children the entirety of their African culture. Nonetheless, making use of the ontology (ways of being), epistemology (ways of knowing), axiology (values), virtues (standards), and principles of an African worldview will engulf Black children in a way of life that is inherently in them and expose all children to different ways to be with the world, particularly if preserving life on this planet is an actual priority. Infusing the Nguzo Saba alone would change the operational aspects of schools–parent and family engagement, climate and culture, scheduling, meals–as well as curriculum (what gets taught), pedagogy (how “the what” gets taught), and assessment. Embracing Afrocentricity is a possibility for revolutionizing our public school system.

Leave a Comment

Check me out on EPISODE 8: #FreeGrace – #StopBrutalizingBlackBodiesPodcast Hosted By #LisaDurden